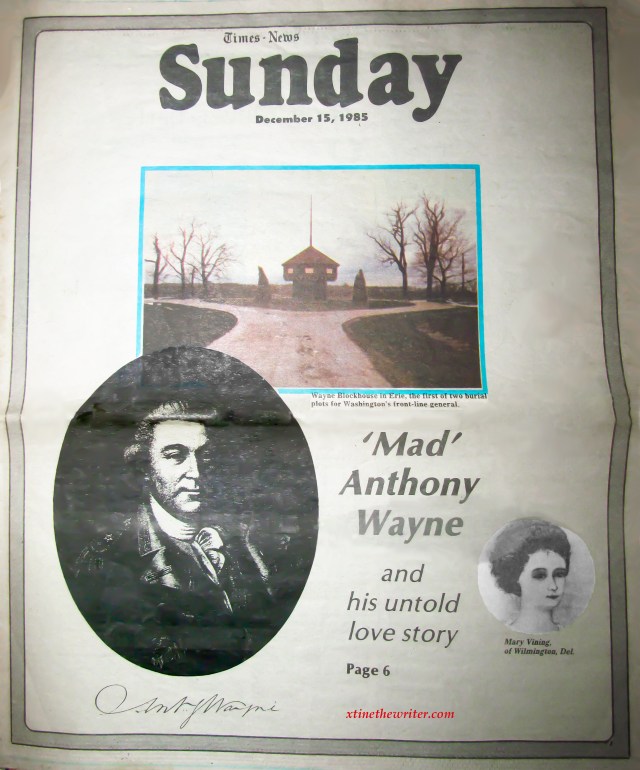

Published Dec. 15, 1985 in the Erie Times News Sunday magazine Feature story by Christine Lorraine Morgan

Revised/typed on Dec. 16, 2025

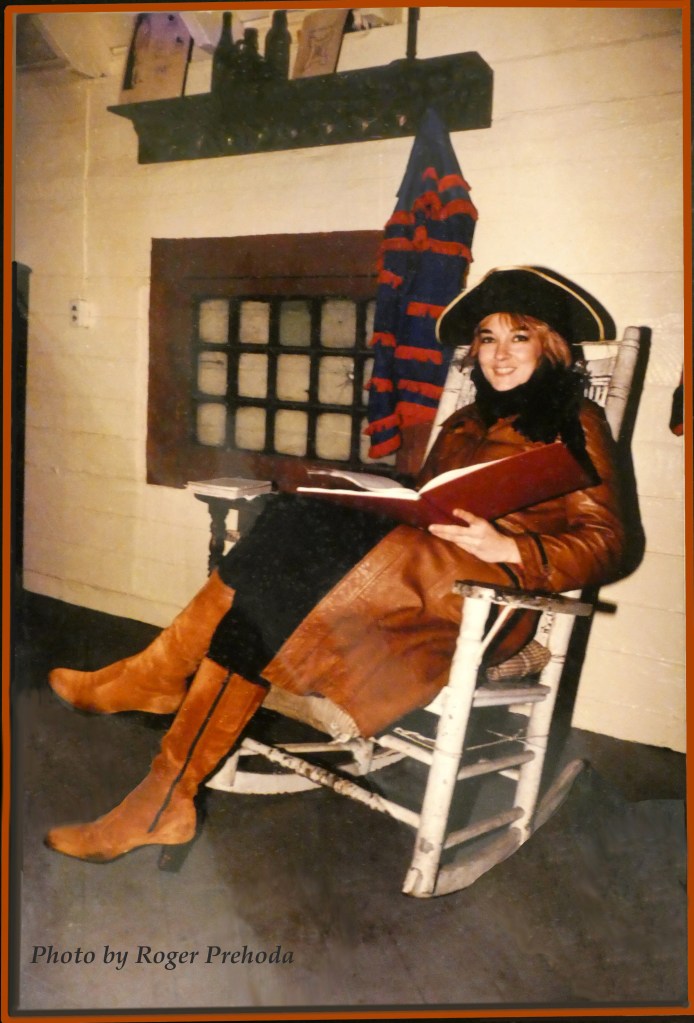

Author Christine Lorraine Morgan smiles while conducting research on General Anthony Wayne inside of the Wayne Blockhouse in Erie, PA

* * * * * * *

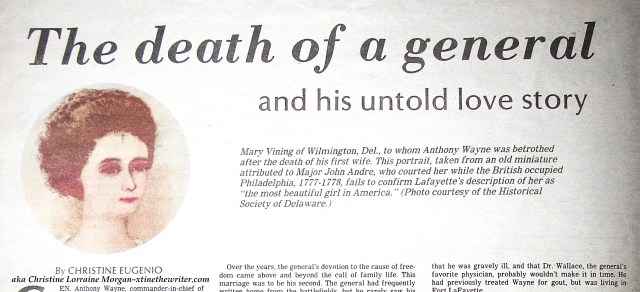

This image shows Mary Vining of Wilmington, Del., to whom Anthony Wayne was betrothed after the death of his first wife. This portrait was taken from an old miniature attributed to Major John Andre, who courted her while the British occupied Philadelphia 1777-1778. General Lafayette described her as “the most beautiful girl in America.” (Photo courtesy of the Historical Society of Delaware.)

General Anthony Wayne, Commander-in-Chief of the United States Army, died and was buried at the foot of the flagpole at Fort Presque Isle, Erie, PA on Dec. 15, 1796 ~ 189 years ago today (12/15/1985)

Most people are familiar with the story of how, 13 years after his death, Wayne’s body was removed from its grave by his son to be transported to a 2nd burial site. But because the body was barely decomposed, Wayne’s corpse was boiled to separate the bones so that transportation of his father’s partial remains to a location nearly 400 miles away would be possible

But few people know that Wayne was on his way to Radnor to wed when he died of a recurring infection stemming from gout.

Instead of being married to the woman who was waiting for him, Wayne was buried at a time when the natural shoreline of Presque Isle bay still bordered upon Garrison Hill at the foot of Wayne Street, the location of Fort Presque Isle.

Blockhouse replica at its dedication in 1880. Note how the bay came right up to the back of the structure. In 2025, that is all manmade landfill and the bay is quite a ways north from this original shoreline.

* * * * * * *

What follows is the rest of General “Mad” Anthony Wayne’s story as conveyed through historical letters, documents, books and other sources available at the Erie County Historical Society in the 1980s.

Nov. 17, 1796 ~ Fort Presque Isle

The small gathering of men stationed at Fort Presque Isle was assembled in dress uniform in honor of the anticipated arrival of a great war hero and soldier. The atmosphere was somewhat relaxed, the area had been free of fighting since the Indians burned the original French fort in 1762.

The frigid early sun bathed the nearly frozen shore in icy pastel tones, and the smell of winter was heavy on Garrison Hill.

At morning formation post commander Captain Russell Bissell announced to his men that General Anthony Wayne, Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Army, would be landing at Fort Presque Isle within the next 24 hours.

Traveling across Lake Erie aboard the sloop Detroit, Wayne had been on his way home to his estate in Waynesborugh to retire from his long military career. Wayne had just completed the last assignment he intended to accept and thoughts of a comfortable life of leisure and love were guiding him home.

Lake Erie’s shoreline in December is frigidly unwelcoming

He was planning to marry world-renowned beauty Mary Vining, for whom he had waited years to wed.

But an old leg wound, often characterized as gout, had become infected, and the infection had eventually spread to Wayne’s stomach. He was forced to put his plans to travel on horseback from Fort Presque Isle to Radnor on hold while he was treated at the fort for the terrible infection, which was causing him agonizing pain.

As he tried to relax in his berth aboard the sloop Detroit, Wayne struggled to believe his physique had deteriorated to this point. He was fearless, indestructible. By scaling walls of granite with bayonet in hand, Wayne was the one who had led the dramatic victory at Stony Point, NJ, a victory which turned the tide of the Revolutionary War.

That notorious battle had been won without firing a single shot at the enemy. It was regarded as one of the greatest advances in history, and popularized Wayne with the American public. It also made him feared by the British.

Wayne was revered by the Indians as well for having dealt with them fairly. He helped them resettle in the Midwest, while obtaining the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Kentucky for America, and made sure that treaties were upheld after they were signed.

Over the years, the general’s devotion to the cause of freedom came above and beyond the call of family life.

Wayne had frequently written home from the battlefields, but he rarely saw his two children or his wife, Polly. She had died at home of natural causes in 1795, while Wayne was away drilling his men. By the time he could have reached home to attend her funeral, she was already buried.

Seventeen years before Polly’s death, Wayne had been introduced by General Lafayette to Mary Vining, a delicate 19-year-old. He was immediately smitten and wrote to Vining often.

Because Wayne was already married, Vining rejected his friendship and often did not respond to his letters. Still, she liked Wayne and consistently rejected the advances and proposals of other suitors.

A year after his wife’s death, Vining accepted Wayne’s marriage proposal, and the 38-year-old bride-to-be commenced making wedding preparations. The couple chose a stately mansion in New Castle, PA that would serve as their winter home. Although this marriage was to be Wayne’s second, it was perfectly acceptable socially because he had been a bereaved widower for an appropriate amount of time.

Wayne was 51 when Vining accepted his marriage proposal, a commitment that had filled him with an inflated sort of emotional invigoration. He found himself looking forward to retirement and a quiet new life with Vining.

But, in February of 1796 Wayne had been asked by President George Washington to lead one last mission, a request that sent his plans for a peaceful existence into a state of upheaval. Thus, he and Vining mutually agreed to postpone the wedding for the good of their country.

Now, just shy of his 52nd birthday, which would occur on New Year’s Day, Wayne was on his way home for the wedding. He was trying to keep a positive outlook through the excruciating pain in his gut that was holding him down, but that task was growing more difficult by the hour.

Many of the men at Fort Presque Isle had fought under the general’s command in the Revolutionary War, and had silently rejoiced at their leader’s upcoming marriage and retirement. He certainly deserved some peace and happiness in his life, they reckoned.

General Anthony Wayne, 1745-1796

Nov. 29, 1796 ~ Fort Presque Isle

“Sir:

“…No boat has yet arrived from Pitt or Franklin. I hear Silks is nigh, and I shall expect his boat to LeBoeuf in one day, if the ice does not prevent. We have had a most severe spell of stormy weather, with extreme cold, so much so that this harbor is froze almost over, and the lake is considerably near the land.

“…I can inform you that the Commander-in-Chief arrived at this post on the 18th in company with Col. Kirkpatrick, Capt. De Butts and the Gen., has been exceedingly ill ever since his arrival, but is now a recovering. I expect in a few days he will be on his way to Pitt…

“I am Sir

Your Obed Serv

R. Bissell Capt.

2nd Regt.

P.S. — Doct’r Balfour will write you by Col. Kirkpatrick ” (1).

Dec. 14, 1796 — Fort Presque Isle

Wayne’s condition was grim. Much to the shock of the men at the fort, their hero had been carried off the boat the day of his arrival four weeks ago. The captain had stationed Wayne in the second story of the blockhouse where he’d remained this entire time.

Although the treacherous wind on this day reached a near-deafening pitch, in between howls from the relentless gusts, the troops caught haunting shrieks of agony from the general wafting through the early evening twilight.

Word had circulated throughout the fort that Wayne was gravely ill. On top of that, the general was emphatically requesting his preferred physician, Dr. Wallace, who was residing at Fort LaFayette nearly 100 miles away.

Dr. George Balfour was the only military physician who was able to reach the dying man’s bedside through the thick woods of Pennsylvania in the freezing temperatures. Balfour did everything he possibly could — bled his patient twice a day, and administered whiskey as a stimulant when the loss of blood weakened the dying military leader.

When it dawned on Wayne that he would travel no further, he fought back the pain long enough to convey instructions to Captain Bissell. Wayne told the younger officer that he was near his death, took his hand, and requested burial on the hill at the foot of the fort’s flagpole. (The site to which he referred was on Garrison Hill, where a 19th century reconstruction of the original blockhouse presently sits.)

It was challenging for the soldiers stationed at Presque Isle to grasp that one of the toughest generals to fight for American independence was about to die of gout, and not from enemy fire in battle. And just when he was on his way home to be married and live out the rest of his life with the woman of his dreams.

But then again, it seemed as though the hand of fate had a tendency to deal some twisted cards to Anthony Wayne.

Most everyone in the military had heard of the Battle at Germantown, Pa., and Wayne’s leading role in it. During that 1777 assault on the British, a musketball had ripped into Wayne’s hand, cannon fire had torn across his foot, and his horse had been shot out from under him. But Wayne and his brigade had successfully hit their targets, even as another American general became befuddled by whiskey and led his own troops astray in the fog.

They wound up attacking their own Colonial soldiers, a blunder so great that it upset the entire balance of the overall offensive strategy.

The drunken general was tried by court martial and cashiered for his part in allowing a near-victory to become a total loss. Wayne summed up the episode by saying: “Fortune smiled on us for three full hours, the enemy were broke, dispersed, and flying in all quarters — we were in possession of their whole equipment, together with their park…confusion ensued, and we ran away from the arms of victory open to receive us.”

Dec. 15, 1796 — Fort Presque Isle

“Dear Sir:

“I should have answered your favour full by the last post had I not expected Col. Kirkpatrick would after have set out for Pitt and by him I intended to write — he however was unfortunately detained by our General’s being violently attacked with the gout in his stomach and bowels which after great suffering we have to lament — occasioned his Death last night — his sufferings for several days past have indeed been extreme…

“I am with great esteem

Your Obed Serv

George Balfour” (3)

Image credit: McLaughlin Archives

* * * * * * *

The news of the great man’s passing was mourned throughout the colonies. Many remembered Wayne for his strong character and looks, others who knew him better might have recalled some of the misfortunes that seemed to seek him out.

One such example was how his leg wound that became infested with gout was allegedly the result of musket fire from an American sentry.

Or one might also consider Wayne’s dubious “reward” for liberating the state of Georgia. The plantation he had been endowed with was a financial nightmare. The 830 acres, wrote Glenn Tucker in his book “Mad Anthony Wayne and the New Nation:” “was in a good rice area on the Little Setilla River … it has been highly profitable when tended before the war. Neglect had given it back to nature and the swampland jungles had encroached … Wayne’s failure as a Southern planter resulted from no more than the rice crops did not bring in enough money to meet the payments of interest and principal due on his loans.”

And who could forget the mutiny that unfolded on Wayne’s 35th birthday?

On that day, young General Wayne was faced with 2,000 men who had grown tired of sub-human living conditions with no pay. In celebration of New Year’s Day, the soldiers had been allowed extra rations of rum, which caused them to become easily incited by several ex-British sergeants.

No matter how frustrated and angry the men became, though, they insisted that Wayne be their negotiator. Under his skillful leadership, the matter was peacefully resolved.

Summer 1809 — Fort Presque Isle

Col. Isaac Wayne arrived to transport his father’s remains to their final resting place 13 years after his burial in Erie. It was Isaac’s intention to transport the remains to Radnor, Pa. He had made the lengthy and treacherous journey in a one-horse sulky because he wouldn’t need much space to transport his father’s ashes.

Isaac quickly enlisted the assistance of Dr. J. G. Wallace to open the grave before a small crowd of workers and curious onlookers. When Wayne’s coffin was opened, the macabre sight that met their eyes caused audible gasping by those gathered: The general’s body was just about perfectly preserved, except for the gout-ridden leg.

This unanticipated turn of events indicated an immediate need to change plans. There was no way his father’s 13-year-old corpse would fit into Isaac’s sulky for the arduous 388-mile journey through the untamed Pennsylvania wilderness.

Wayne’s uniform was tattered but partially intact, and only one of his knee-high black leather boots had endured the years because the boot on his infected leg had rotted away. One bold local citizen asked Isaac if he might have the general’s good boot, being that he was a great admirer of Wayne’s military career, a wish Isaac granted hastily to ensure the man’s rapid departure.

After consorting with Isaac, Dr. Wallace then spoke with the fort’s commanding officer, and was given one of the army’s large wagons used to transport heavy items. He headed into the town of Erie, where he spoke with the owner of a local foundry. An hour later Wallace returned with an oversized cast iron kettle, measuring two feet in diameter, with the metal framework to use it over an open fire outdoors.

After a small detail of men had set the kettle up, they assisted Wallace in a bizarre task that would enable Isaac to return home with his father’s bones.

A roaring fire was built, the kettle was filled with water, and General Anthony Wayne’s enduring remains were then placed in the pot and boiled to separate the flesh from his bones.

The general’s clothing, military insignias and other remnants were then placed with the tools used by the doctor to perform the unpleasant task. All were respectfully returned to the original gravesite.

Wayne’s bones were packed into Isaac’s sulky so they could be taken home to be buried.

General Wayne’s second burial took place on July 4, 1809 in Radnor. It was attended by a great many people from Philadelphia and the surrounding area.

This great hero’s two funerals were 13 years apart. And despite the passage of centuries, tales about Wayne still live on in Pennsylvania folklore.

It is said that some of the General’s bones fell out of Isaac’s sulky during the challenging journey of crossing through the unknown territories and terrains of Pennsylvania in 1809. Because of if this, Wayne surfaces once a year to look for his bones.

The tale is that on New Year’s Eve as the clock crosses to midnight, his birthday, Wayne rises up and mounts his horse, Nancy. Together they ride furiously across the commonwealth of PA, from his grave in Radnor to the blockhouse in Erie, searching for his missing bones.

Editor’s note: “Free-lance writer Christine Lorraine Morgan became interested in General Anthony Wayne and his link to Erie during her early school years here. She is a Vietnam veteran, today lives on the Erie street named for Wayne.”

this is a great story of a great man.