by Christine Lorraine Morgan, Dec. 3, 2025

A proposed city of greatness was mapped out on paper in the late 1790s, and the area in which the future settlement was anticipated sat nestled in the wilderness at the mouth of Four Mile Creek.

To help stimulate the town’s development, a shipyard was established, and it is said that the first commercial vessel to ever sail Lake Erie was built there in around 1797.

However, historical accounts indicate that the proposed town never really reached the popularity status its developers were anticipating due to a lack of enthusiasm and other uninspiring factors, thus the plan was abandoned.

Three decades later, two brothers, Thomas and Michael Crowley, arrived in Erie from Ireland and ended up purchasing 399 acres along the eastern Lake Erie shoreline in 1827. This parcel included the area where Four Mile Creek empties into the lake, the exact area in which the proposed great city never took hold.

Known for being very industrious men with unfaltering energy, the Crowley brothers cleared thick timber, wild ravines and untamed foliage, and began to cultivate the area. As their work progressed, they divided their pristine farmland into two parcels. The northern tract along the lakeshore was Thomas’, and the southern half of the land was designated as Michael’s.

Around this time, a sprawling apple orchard was planted just east of Four Mile Creek along the bank of Lake Erie. As they matured, these graceful trees received excellent care and, in turn, provided much-welcome shade and an abundance of juicy apples over the decades.

Due to its relaxing location and bountiful apple orchard, this area of what is now Lawrence Park in Erie County began to attract parties of local picnickers seeking a lakeside setting.

After Thomas Crowley’s death, the lakeside land was inherited by Richard Crowley, his son, who died shortly thereafter. Richard’s wife and daughters then inherited the property and continued to reside at the family homestead.

In the early spring of 1887, J. J. Lang and C. H. Rabe of Erie expressed an interest in purchasing the lakefront property. They offered a price that was considered more than fair by the neighboring farmers, and the sale was executed. A total of 13 acres, which comprised all of the Crowley farm’s lakefront, was deeded over to Lang and Rabe. The parcel that was purchased also included the mouth of Four Mile Creek and the grove and orchard areas.

Numerous workers were hired to install a smooth, wide avenue starting at the Lake Road, running along Four Mile Creek’s east bank to Lake Erie.

A broad, sturdy wooden pier was constructed from the shore extending northward into water where it was deep enough to offer passenger steamers and sailing yachts a safe landing place. Then the overgrown bank was cleared to create an easy incline running from the freshly leveled ground to the dock.

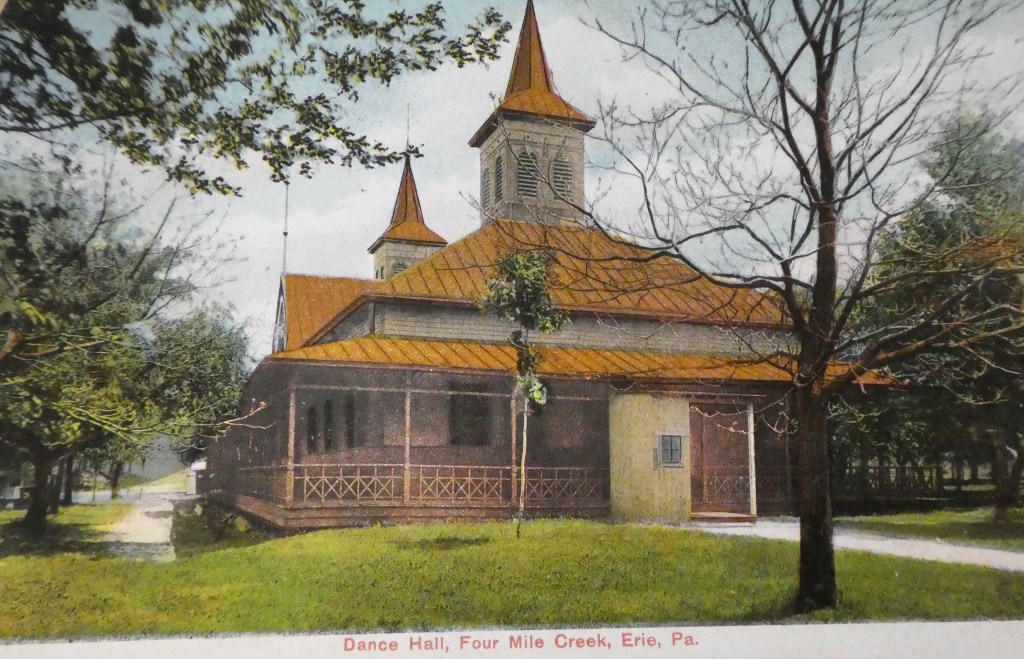

Before the dust had barely cleared on this phase of the development, a state-of-the-art dance hall/pavilion with an attractive, showy exterior was built. This seemed like a logical next step since the park was now easily accessible by both water and land.

This vibrant building, measuring 61′ x 122′, was designed for large numbers of people to dance, and it was enveloped by a wide veranda for guests to enjoy the fresh lake air or a leisurely stroll in between waltzes. Also contained within its brand new walls were a reception room, closets, a smoking room and an array of dressing rooms.

Meticulous planning was put into this dance pavilion, and it was well-ventilated with decent lighting. It sat detached from the park’s other building, a refreshment hall, which was continuously well-stocked with ample quantities of the best refreshments the local market could supply.

Finally, in June of 1887, this water’s edge haven was ready to open its doors to the public. Named Grove House Park, it received an overabundance of positive attention in local newspapers and flourished from its big-splash beginning. The Grove House’s primary competitor was one-year-old Waldameer park, a west Millcreek lakeside trolley destination which was created by the Erie Electric Motor Company.

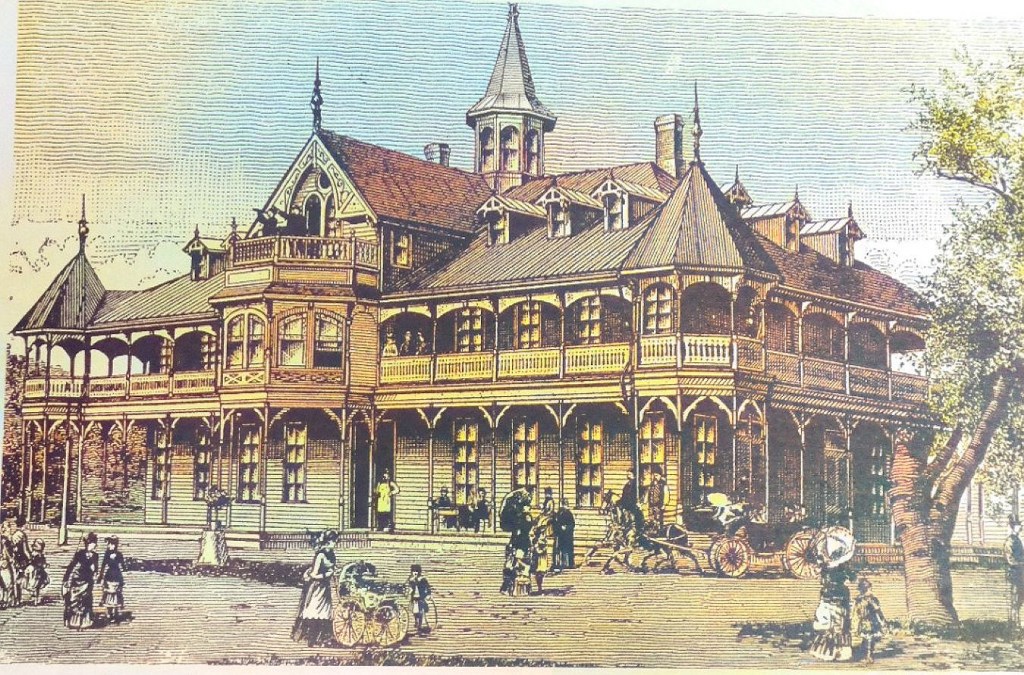

Due to Grove House Park’s remarkable overnight success, plans to build an extravagant three-story French-style hotel were put into action. This was erected about 100 yards south of the shoreline so that it faced the busy steamboat landing. It featured numerous dormer windows, gables, and a tower surmounted on each of its four corners with a cupola rising from the center of each one.

From the upper floors, a dazzling view of the open water was visible in front, and to the left, the towering spires and domes of Erie’s church steeples and fine buildings could be easily observed. In the back and to the right of Grove House were thriving vineyards, orchards, gardens and other delights of nature that stretched into forest covered-hills. This green-laden pastoral stillness coupled with breathtaking scenery were so astounding that those who witnessed this sight did not soon forget.

To further embellish Grove House’s desirability as a getaway resort, a sprawling two-story veranda was wrapped around the entire 60′ x 100′ building. All told, there were 60 well-illuminated, stylish sleeping apartments within the hotel’s ornate walls. Each was as nicely ventilated, decorated and comfortable as the next.

These large, airy rooms were entirely furnished and many of them were connected by folding doors. Wide halls extended throughout the structure that connected its numerous guests with whatever facilities and amenities they sought.

On the first floor, guests would find a sizeable dining room, lunch room and a generously stocked kitchen outfitted for all possible events and endeavors.

Both wings on the second floor were set up to be used as private dining rooms if an occasion arose where a guest wished for a bit of one-on-one or solitary time.

J. Lang bought out Mr. Rabe in 1889, and it was announced in the local newspaper that Lang and his family intended to move in to the Grove House in the spring of 1890 so he could devote his time, energy, and financial support to the place.

Also in 1890 it was said that Grove House Park’s stellar reputation was heard of in major cities 200 miles away.

That same year, whispers of big transportation plans began to cause quite a hubbub. In February 1890 the local grapevine was buzzing with rumors that the Electric Motor Company might extend its trolley route to Four Mile Creek through Wesleyville. “The people of Erie will gladly hail this news,” stated an article by the Erie Morning Dispatch. “In fact, if a road to the Head is found to be an extremely paying investment, why should not a road to Four Mile Creek meet with the same financial success…

“…Let us hope that this will prove no idle rumor and that the spring will see the electric railway in full operation between the city and the famous resort, Grove House Park, which, by the way, will be opened for the entertainment of guests by the first of the coming May.”

The rumors became fact shortly thereafter, when the trolley line was extended to the Four Mile Creek area.

As Grove House’s popularity continued to advance, it became apparent that more power was needed to fuel the resort, which was open from early May into September. Its annual closing date was determined by weather conditions, the longer temperatures remained favorable, the further into the year the facilities continued to stay open.

Thus a 900-foot deep gas well was successfully sunk several years after the hotel opened. The new fuel-providing well offered the sought-after getaway spot with plenty of energy for both heating and lighting purposes. This ensured the comfort of its multitude of new vacationers and returning guests.

By 1902 Grove House’s gas well technology was on the cusp of becoming obsolete as electricity had began to light up the City of Erie in the 1880s. Due to its rural location four miles east of the city, the comforts of electricity had not yet been extended to the resort’s east side zone, and wouldn’t reach there for another eight to 10 years.

As the 1902 Labor Day weekend drew to a close, most of the guests at Grove House had already headed home to start their work week and settle back into their rigidly-cast turn-of-the-century lifestyles. A dozen or so guests remained and a handful of staff because the resort had not yet closed down for the season.

Due to the heavy influx of leisure-seekers for the last official weekend of summer, Grove House’s gas well flow was running weak from being overtaxed. The resort’s kitchen staff had not noticed the waning burner flames on the resort’s five stove units during the weekend’s food prep process, so at the end of each day the pilot lights were left on, as was customary. Relighting a pilot light in those complex gas stoves was not the easiest of tasks, and was avoided whenever possible. Pilot lights were only extinguished when the season ended, or the gas well was indicating a dangerously low supply flow.

Because of low gas levels on this holiday weekend, a problem was created in the kitchen where five large iron stoves were utilized daily to feed guests. The pilot light in stove #5 went out due to a very low gas flow shortly after most guests had retired for the night. Five hours later at around 4 a.m., when the gas well supply returned to its normal level, a stream of natural gas mingled with the four lit pilot flames that had remained burning throughout the night.

This unlit gas jet situation eventually erupted into a minor explosion at about 4:30 a.m. inside of the resort’s roomy kitchen. Several sleeping guests almost woke up from the disruption, but due to their distance from the kitchen area of the hotel, the sound was not powerful enough to penetrate their layers of deep sleep. It had been a long weekend of dancing and imbibing, which can result in dulled senses while asleep.

In elaborate detail, the local newspaper presented the Grove House Park fire story later that day. “Shortly before 5 o’clock this morning, Mrs. Margaret McCann, the cook, was awakened by smoke pouring into her room on the second floor and, on making an investigation, found that a good portion of the south side of the building, first story, in the vicinity of the kitchen, was all in flames,” reported the Sept. 2, 1902 Erie Daily Times.

“She ran at once to the rooms of Mr. and Mrs. H. T. Foster, the landlord and landlady, and awakened them and then she went to the rooms of all the other inmates who were, likewise aroused, and they came out and down stairs with scarcely anything on but their night clothes.”

Foster and employee Scott Sterrett attempted to extinguish the spreading flames with containers of water near the kitchen, but upon realizing their goal was futile, they abandoned the job and instead turned their efforts toward helping others escape.

Landlady Mrs. Foster had been ill for “nearly two weeks and was threatened with typhoid fever,” continued the Erie Times article. “She was carried down and out with only an old dress over her night clothes and later when the excitement had subsided she was taken to the Crowley Farm house nearby. Her two children, Marie age 11 and Dorothy age 7, were so frightened that they had to be carried down and out with only their night clothes on,” according to the Erie Daily Times piece.

At 5:07 a.m. Erie Fire Chief John McMahon received the call about Grove House burning, and about 25 minutes later the fire-fighting apparatus reached the scene. “The creek was hurriedly damned at the bridge on the Lake Road, where the steamer was stationed and a line of hose, several hundred feet long, was stretched to the burning building, and soon a stream was playing on the fire, but, of course, it was too late and the structure was, in a short time, only a mass of smoldering ruins,” the Times article continued.

Although the Grove House, one of the most poetically breathtaking structures in Erie County, had burned to the ground, other buildings in the park survived the inferno. Those were the dance hall, bowling alley, refreshment pavilion and the round house. Speculation at the time was that if the wind had come from the east that morning instead of the west, more buildings would have been lost.

Those staying at the Grove House on that fateful night lost all of their possessions, for the most part, as the building was declared a total loss. “Mr. and Mrs. O. P. Hall lost nearly everything, as did Mr. and Mrs. Irwin; Mrs. McCann managed to save several articles, one of which was her sewing machine.” The Times News article added that those who helped others escape the blaze and helped subdue the fire were O. R. Williams and Wm. D. Dorsey.

Today, in 2025, no visible trace of Grove House Park remains behind to tell the bewitching tale of the magnificent times that were enjoyed there. No ashes, no remnants, no clues of its glorious existence have been unearthed to help historians piece together this grand puzzle from the past.

But there are possible clues and pieces of potential evidence that have begun to surface from beneath the constantly changing Lake Erie shoreline. During the summer of 2025 an intense search revealed some very interesting discoveries, some of which will be revealed in the next installment of “THE STORY OF GROVE HOUSE PARK, the Exquisite Lake Erie Haven in Lawrence Park that Vanished: Christine’s Chronicles.”

Such a dramatic end to a dramatic building! So sorry it is gone forever. I imagine there was nothing quite like it in the surrounding cities in the tri-state area at the time. Our piece of Lake Erie is very unique. Thanks for all the detail you uncovered. Grove House was such a grand lady in it’s time.

Joanne Druzak